Trade Balance

原文

America’s Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling The Nation Out From Under Us. Here’s A Way To Fix The Problem–And We Need To Do It Now.

- By Warren E. Buffett Carol J. Loomis

- November 10, 2003

(FORTUNE Magazine) – I’m about to deliver a warning regarding the U.S. trade deficit and also suggest a remedy for the problem. But first I need to mention two reasons you might want to be skeptical about what I say. To begin, my forecasting record with respect to macroeconomics is far from inspiring. For example, over the past two decades I was excessively fearful of inflation. More to the point at hand, I started way back in 1987 to publicly worry about our mounting trade deficits–and, as you know, we’ve not only survived but also thrived. So on the trade front, score at least one “wolf” for me. Nevertheless, I am crying wolf again and this time backing it with Berkshire Hathaway’s money. Through the spring of 2002, I had lived nearly 72 years without purchasing a foreign currency. Since then Berkshire has made significant investments in–and today holds–several currencies. I won’t give you particulars; in fact, it is largely irrelevant which currencies they are. What does matter is the underlying point: To hold other currencies is to believe that the dollar will decline.

Both as an American and as an investor, I actually hope these commitments prove to be a mistake. Any profits Berkshire might make from currency trading would pale against the losses the company and our shareholders, in other aspects of their lives, would incur from a plunging dollar.

But as head of Berkshire Hathaway, I am in charge of investing its money in ways that make sense. And my reason for finally putting my money where my mouth has been so long is that our trade deficit has greatly worsened, to the point that our country’s “net worth,” so to speak, is now being transferred abroad at an alarming rate.

A perpetuation of this transfer will lead to major trouble. To understand why, take a wildly fanciful trip with me to two isolated, side-by-side islands of equal size, Squanderville and Thriftville. Land is the only capital asset on these islands, and their communities are primitive, needing only food and producing only food. Working eight hours a day, in fact, each inhabitant can produce enough food to sustain himself or herself. And for a long time that’s how things go along. On each island everybody works the prescribed eight hours a day, which means that each society is self-sufficient.

Eventually, though, the industrious citizens of Thriftville decide to do some serious saving and investing, and they start to work 16 hours a day. In this mode they continue to live off the food they produce in eight hours of work but begin exporting an equal amount to their one and only trading outlet, Squanderville.

The citizens of Squanderville are ecstatic about this turn of events, since they can now live their lives free from toil but eat as well as ever. Oh, yes, there’s a quid pro quo–but to the Squanders, it seems harmless: All that the Thrifts want in exchange for their food is Squanderbonds (which are denominated, naturally, in Squanderbucks).

Over time Thriftville accumulates an enormous amount of these bonds, which at their core represent claim checks on the future output of Squanderville. A few pundits in Squanderville smell trouble coming. They foresee that for the Squanders both to eat and to pay off–or simply service–the debt they’re piling up will eventually require them to work more than eight hours a day. But the residents of Squanderville are in no mood to listen to such doomsaying.

Meanwhile, the citizens of Thriftville begin to get nervous. Just how good, they ask, are the IOUs of a shiftless island? So the Thrifts change strategy: Though they continue to hold some bonds, they sell most of them to Squanderville residents for Squanderbucks and use the proceeds to buy Squanderville land. And eventually the Thrifts own all of Squanderville.

At that point, the Squanders are forced to deal with an ugly equation: They must now not only return to working eight hours a day in order to eat–they have nothing left to trade–but must also work additional hours to service their debt and pay Thriftville rent on the land so imprudently sold. In effect, Squanderville has been colonized by purchase rather than conquest.

It can be argued, of course, that the present value of the future production that Squanderville must forever ship to Thriftville only equates to the production Thriftville initially gave up and that therefore both have received a fair deal. But since one generation of Squanders gets the free ride and future generations pay in perpetuity for it, there are–in economist talk–some pretty dramatic “intergenerational inequities.”

Let’s think of it in terms of a family: Imagine that I, Warren Buffett, can get the suppliers of all that I consume in my lifetime to take Buffett family IOUs that are payable, in goods and services and with interest added, by my descendants. This scenario may be viewed as effecting an even trade between the Buffett family unit and its creditors. But the generations of Buffetts following me are not likely to applaud the deal (and, heaven forbid, may even attempt to welsh on it).

Think again about those islands: Sooner or later the Squanderville government, facing ever greater payments to service debt, would decide to embrace highly inflationary policies–that is, issue more Squanderbucks to dilute the value of each. After all, the government would reason, those irritating Squanderbonds are simply claims on specific numbers of Squanderbucks, not on bucks of specific value. In short, making Squanderbucks less valuable would ease the island’s fiscal pain.

That prospect is why I, were I a resident of Thriftville, would opt for direct ownership of Squanderville land rather than bonds of the island’s government. Most governments find it much harder morally to seize foreign-owned property than they do to dilute the purchasing power of claim checks foreigners hold. Theft by stealth is preferred to theft by force.

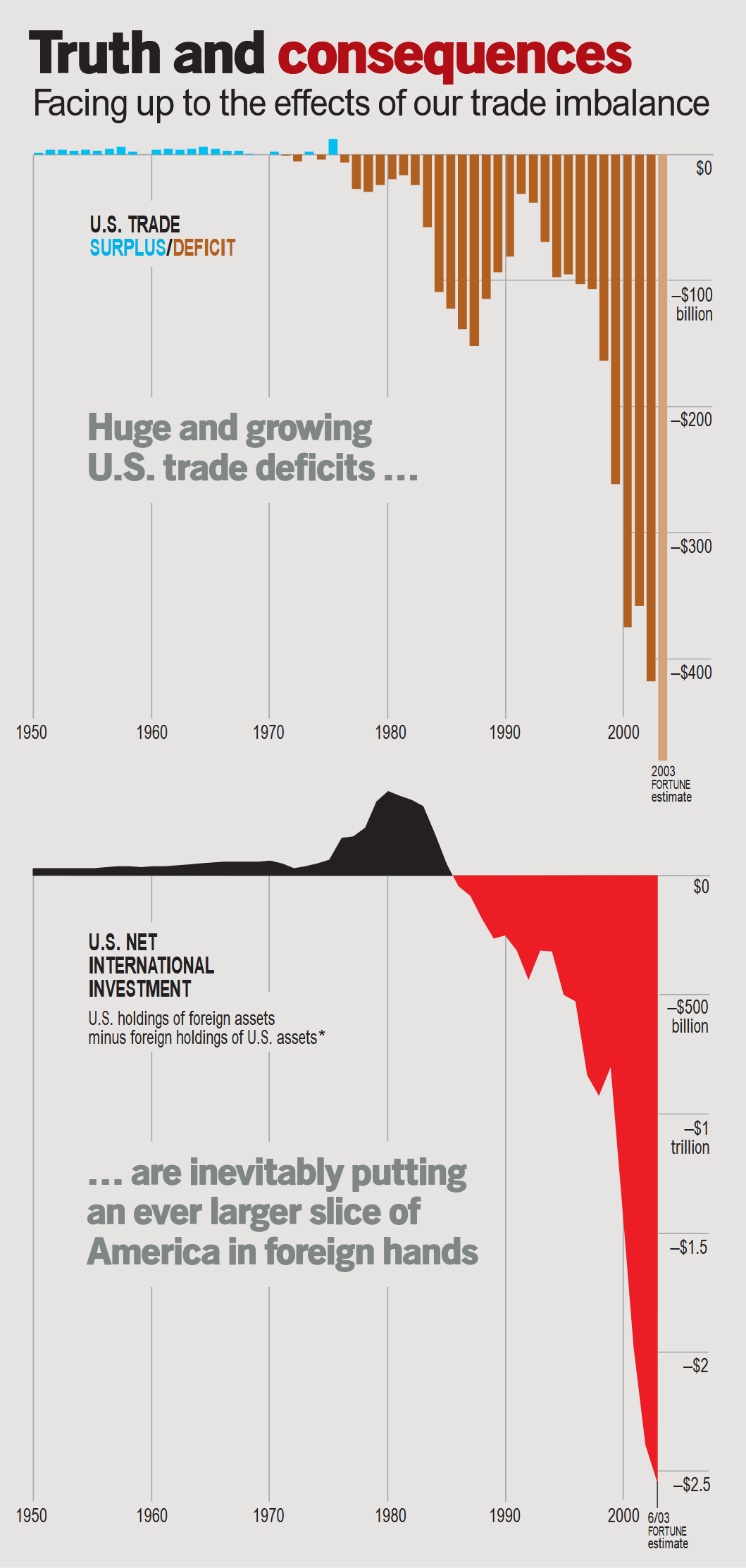

So what does all this island hopping have to do with the U.S.? Simply put, after World War II and up until the early 1970s we operated in the industrious Thriftville style, regularly selling more abroad than we purchased. We concurrently invested our surplus abroad, with the result that our net investment–that is, our holdings of foreign assets less foreign holdings of U.S. assets–increased (under methodology, since revised, that the government was then using) from $37 billion in 1950 to $68 billion in 1970. In those days, to sum up, our country’s “net worth,” viewed in totality, consisted of all the wealth within our borders plus a modest portion of the wealth in the rest of the world.

Additionally, because the U.S. was in a net ownership position with respect to the rest of the world, we realized net investment income that, piled on top of our trade surplus, became a second source of investable funds. Our fiscal situation was thus similar to that of an individual who was both saving some of his salary and reinvesting the dividends from his existing nest egg.

In the late 1970s the trade situation reversed, producing deficits that initially ran about 1% of GDP. That was hardly serious, particularly because net investment income remained positive. Indeed, with the power of compound interest working for us, our net ownership balance hit its high in 1980 at $360 billion.

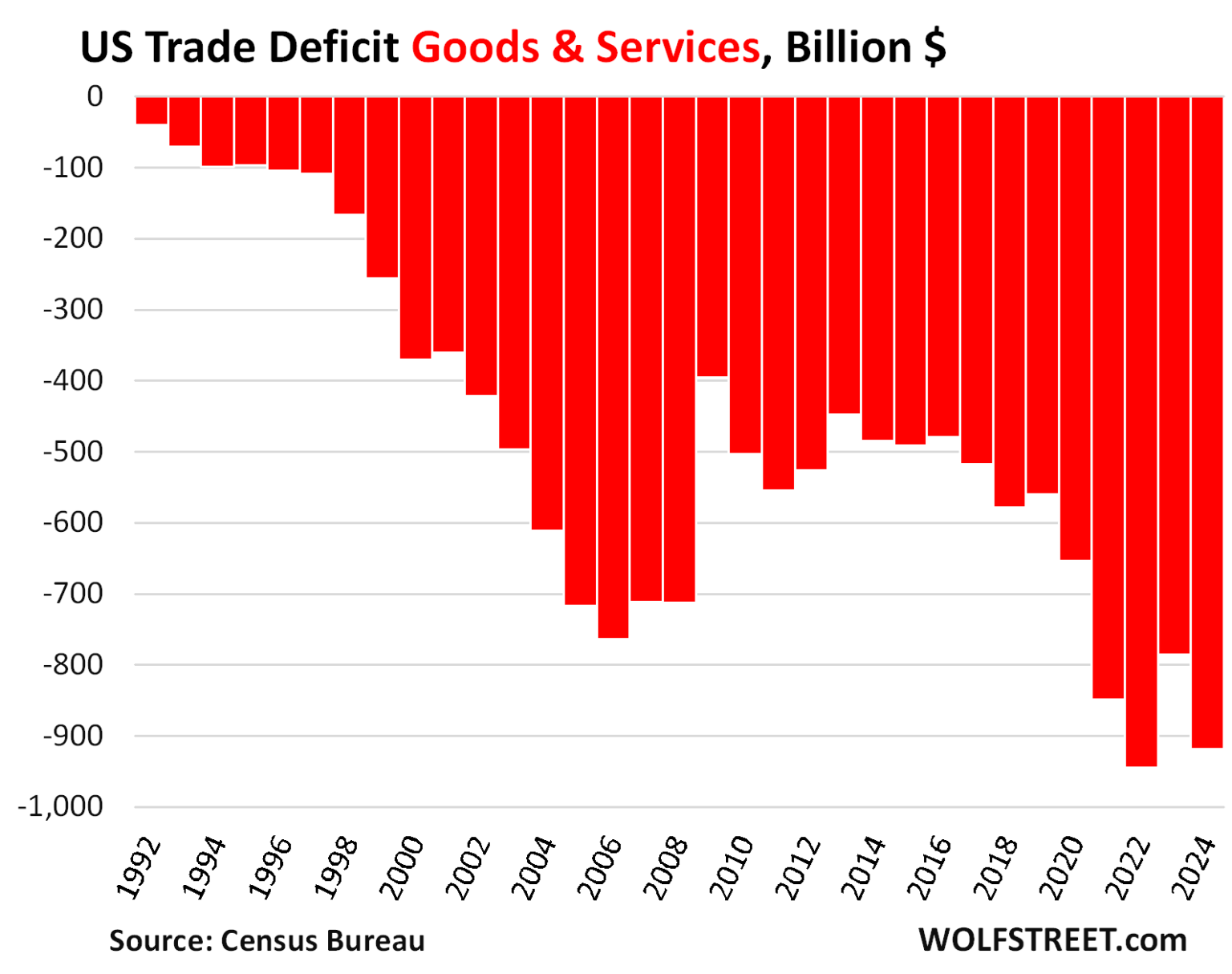

Since then, however, it’s been all downhill, with the pace of decline rapidly accelerating in the past five years. Our annual trade deficit now exceeds 4% of GDP. Equally ominous, the rest of the world owns a staggering $2.5 trillion more of the U.S. than we own of other countries. Some of this $2.5 trillion is invested in claim checks–U.S. bonds, both governmental and private–and some in such assets as property and equity securities.

In effect, our country has been behaving like an extraordinarily rich family that possesses an immense farm. In order to consume 4% more than we produce–that’s the trade deficit–we have, day by day, been both selling pieces of the farm and increasing the mortgage on what we still own.

To put the $2.5 trillion of net foreign ownership in perspective, contrast it with the $12 trillion value of publicly owned U.S. stocks or the equal amount of U.S. residential real estate or what I would estimate as a grand total of $50 trillion in national wealth. Those comparisons show that what’s already been transferred abroad is meaningful–in the area, for example, of 5% of our national wealth.

More important, however, is that foreign ownership of our assets will grow at about $500 billion per year at the present trade-deficit level, which means that the deficit will be adding about one percentage point annually to foreigners’ net ownership of our national wealth. As that ownership grows, so will the annual net investment income flowing out of this country. That will leave us paying ever-increasing dividends and interest to the world rather than being a net receiver of them, as in the past. We have entered the world of negative compounding–goodbye pleasure, hello pain.

We were taught in Economics 101 that countries could not for long sustain large, ever-growing trade deficits. At a point, so it was claimed, the spree of the consumption-happy nation would be braked by currency-rate adjustments and by the unwillingness of creditor countries to accept an endless flow of IOUs from the big spenders. And that’s the way it has indeed worked for the rest of the world, as we can see by the abrupt shutoffs of credit that many profligate nations have suffered in recent decades.

The U.S., however, enjoys special status. In effect, we can behave today as we wish because our past financial behavior was so exemplary–and because we are so rich. Neither our capacity nor our intention to pay is questioned, and we continue to have a mountain of desirable assets to trade for consumables. In other words, our national credit card allows us to charge truly breathtaking amounts. But that card’s credit line is not limitless.

The time to halt this trading of assets for consumables is now, and I have a plan to suggest for getting it done. My remedy may sound gimmicky, and in truth it is a tariff called by another name. But this is a tariff that retains most free-market virtues, neither protecting specific industries nor punishing specific countries nor encouraging trade wars. This plan would increase our exports and might well lead to increased overall world trade. And it would balance our books without there being a significant decline in the value of the dollar, which I believe is otherwise almost certain to occur.

We would achieve this balance by issuing what I will call Import Certificates (ICs) to all U.S. exporters in an amount equal to the dollar value of their exports. Each exporter would, in turn, sell the ICs to parties–either exporters abroad or importers here–wanting to get goods into the U.S. To import $1 million of goods, for example, an importer would need ICs that were the byproduct of $1 million of exports. The inevitable result: trade balance.

Because our exports total about $80 billion a month, ICs would be issued in huge, equivalent quantities–that is, 80 billion certificates a month–and would surely trade in an exceptionally liquid market. Competition would then determine who among those parties wanting to sell to us would buy the certificates and how much they would pay. (I visualize that the certificates would be issued with a short life, possibly of six months, so that speculators would be discouraged from accumulating them.)

For illustrative purposes, let’s postulate that each IC would sell for 10 cents–that is, 10 cents per dollar of exports behind them. Other things being equal, this amount would mean a U.S. producer could realize 10% more by selling his goods in the export market than by selling them domestically, with the extra 10% coming from his sales of ICs.

In my opinion, many exporters would view this as a reduction in cost, one that would let them cut the prices of their products in international markets. Commodity-type products would particularly encourage this kind of behavior. If aluminum, for example, was selling for 66 cents per pound domestically and ICs were worth 10%, domestic aluminum producers could sell for about 60 cents per pound (plus transportation costs) in foreign markets and still earn normal margins. In this scenario, the output of the U.S. would become significantly more competitive and exports would expand. Along the way, the number of jobs would grow.

Foreigners selling to us, of course, would face tougher economics. But that’s a problem they’re up against no matter what trade “solution” is adopted–and make no mistake, a solution must come. (As Herb Stein said, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”) In one way the IC approach would give countries selling to us great flexibility, since the plan does not penalize any specific industry or product. In the end, the free market would determine what would be sold in the U.S. and who would sell it. The ICs would determine only the aggregate dollar volume of what was sold.

To see what would happen to imports, let’s look at a car now entering the U.S. at a cost to the importer of $20,000. Under the new plan and the assumption that ICs sell for 10%, the importer’s cost would rise to $22,000. If demand for the car was exceptionally strong, the importer might manage to pass all of this on to the American consumer. In the usual case, however, competitive forces would take hold, requiring the foreign manufacturer to absorb some, if not all, of the $2,000 IC cost.

There is no free lunch in the IC plan: It would have certain serious negative consequences for U.S. citizens. Prices of most imported products would increase, and so would the prices of certain competitive products manufactured domestically. The cost of the ICs, either in whole or in part, would therefore typically act as a tax on consumers.

That is a serious drawback. But there would be drawbacks also to the dollar continuing to lose value or to our increasing tariffs on specific products or instituting quotas on them–courses of action that in my opinion offer a smaller chance of success. Above all, the pain of higher prices on goods imported today dims beside the pain we will eventually suffer if we drift along and trade away ever larger portions of our country’s net worth.

I believe that ICs would produce, rather promptly, a U.S. trade equilibrium well above present export levels but below present import levels. The certificates would moderately aid all our industries in world competition, even as the free market determined which of them ultimately met the test of “comparative advantage.”

This plan would not be copied by nations that are net exporters, because their ICs would be valueless. Would major exporting countries retaliate in other ways? Would this start another Smoot-Hawley tariff war? Hardly. At the time of Smoot-Hawley we ran an unreasonable trade surplus that we wished to maintain. We now run a damaging deficit that the whole world knows we must correct.

For decades the world has struggled with a shifting maze of punitive tariffs, export subsidies, quotas, dollar-locked currencies, and the like. Many of these import-inhibiting and export-encouraging devices have long been employed by major exporting countries trying to amass ever larger surpluses–yet significant trade wars have not erupted. Surely one will not be precipitated by a proposal that simply aims at balancing the books of the world’s largest trade debtor. Major exporting countries have behaved quite rationally in the past and they will continue to do so–though, as always, it may be in their interest to attempt to convince us that they will behave otherwise.

The likely outcome of an IC plan is that the exporting nations–after some initial posturing–will turn their ingenuity to encouraging imports from us. Take the position of China, which today sells us about $140 billion of goods and services annually while purchasing only $25 billion. Were ICs to exist, one course for China would be simply to fill the gap by buying 115 billion certificates annually. But it could alternatively reduce its need for ICs by cutting its exports to the U.S. or by increasing its purchases from us. This last choice would probably be the most palatable for China, and we should wish it to be so.

If our exports were to increase and the supply of ICs were therefore to be enlarged, their market price would be driven down. Indeed, if our exports expanded sufficiently, ICs would be rendered valueless and the entire plan made moot. Presented with the power to make this happen, important exporting countries might quickly eliminate the mechanisms they now use to inhibit exports from us.

Were we to install an IC plan, we might opt for some transition years in which we deliberately ran a relatively small deficit, a step that would enable the world to adjust as we gradually got where we need to be. Carrying this plan out, our government could either auction “bonus” ICs every month or simply give them, say, to less-developed countries needing to increase their exports. The latter course would deliver a form of foreign aid likely to be particularly effective and appreciated.

I will close by reminding you again that I cried wolf once before. In general, the batting average of doomsayers in the U.S. is terrible. Our country has consistently made fools of those who were skeptical about either our economic potential or our resiliency. Many pessimistic seers simply underestimated the dynamism that has allowed us to overcome problems that once seemed ominous. We still have a truly remarkable country and economy.

But I believe that in the trade deficit we also have a problem that is going to test all of our abilities to find a solution. A gently declining dollar will not provide the answer. True, it would reduce our trade deficit to a degree, but not by enough to halt the outflow of our country’s net worth and the resulting growth in our investment-income deficit.

Perhaps there are other solutions that make more sense than mine. However, wishful thinking–and its usual companion, thumb sucking–is not among them. From what I now see, action to halt the rapid outflow of our national wealth is called for, and ICs seem the least painful and most certain way to get the job done. Just keep remembering that this is not a small problem: For example, at the rate at which the rest of the world is now making net investments in the U.S., it could annually buy and sock away nearly 4% of our publicly traded stocks.

In evaluating business options at Berkshire, my partner, Charles Munger, suggests that we pay close attention to his jocular wish: “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.” Framers of our trade policy should heed this caution–and steer clear of Squanderville.

Warren Buffett is chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway. FORTUNE editor at large Carol J. Loomis, who is a Berkshire shareholder, worked with him on this article.

翻译

美国日益扩大的贸易逆差正在将国家资产变卖殆尽。这是一个解决方案——我们要刻不容缓。

- 作者:沃伦·E·巴菲特(Warren E. Buffett),卡罗尔·J·卢米斯(Carol J. Loomis)

- 时间:2003年11月10日

- 来源:《财富》杂志(FORTUNE Magazine)

我即将针对美国的贸易逆差发出警告,并提出一个补救方案。但首先,我得提及两个你们可能会对我所言持怀疑态度的理由。首先,我在宏观经济方面的预测记录实在算不上辉煌。例如,在过去的二十年里,我曾过度担忧通货膨胀。更切题的是,早在1987年,我就开始公开担忧我们日益增加的贸易逆差——而在座的各位都知道,我们不仅挺过来了,还依然繁荣。所以在贸易战线上,就算我又喊了一次“狼来了”。尽管如此,我还是要再次高呼“狼来了”,而且这次我用伯克希尔·哈撒韦公司(Berkshire Hathaway)的资金作为赌注。直到2002年春天,也就是我快72岁的时候,我还从未买过外币。但从那时起,伯克希尔开始对外币进行大量投资,并在今天持有了几种货币。我不便透露具体细节;事实上,具体是哪种货币在很大程度上并不重要。重要的是其背后的逻辑:持有其他货币,意味着相信美元将会贬值。

无论是作为一个美国人还是一个投资者,其实我都希望这些投资决策被证明是错误的。伯克希尔在货币交易中赚取的任何利润,若与美元暴跌给我们公司及股东在生活其他方面造成的损失相比,都将显得微不足道。

但是,作为伯克希尔·哈撒韦的掌舵人,我的职责是以合理的方式投资公司的资金。我之所以最终决定“坐言起行”、用真金白银去印证我长期以来的观点,是因为我们的贸易逆差已经极度恶化,甚至可以说,我们国家的净资产正以惊人的速度转移到海外。

这种财富转移若持续下去,将导致大麻烦。为了理解其中的原因,请随我进行一次天马行空的想象之旅,去往两个与世隔绝、面积相当且比邻而居的岛屿:挥霍岛(Squanderville)和节俭岛(Thriftville)。土地是这些岛屿上唯一的资本资产,岛上的社会很原始,只需求食物,也只生产食物。事实上,每个居民每天工作8小时,就能生产出足够的食物来维持自己的生存。很长一段时间里,日子就是这样过的。每个岛上的人都按规定工作8小时,这意味着每个社会都是自给自足的。

然而,最终,节俭岛上勤劳的公民决定进行一些严肃的储蓄和投资,他们开始每天工作16小时。在这种模式下,他们继续依靠8小时工作生产的食物生活,但开始将剩余的产量出口到他们唯一的贸易伙伴——挥霍岛。

挥霍岛的居民对这一转变欣喜若狂,因为他们现在可以免于劳作,却依然吃得和以前一样好。当然,这有一个交换条件——但在挥霍岛居民看来,这似乎是无害的:节俭岛居民用食物交换的仅仅是“挥霍债券”(Squanderbonds,当然是以“挥霍币”计价的)。

随着时间的推移,节俭岛积累了大量的这种债券,其核心代表了对挥霍岛未来产出的索偿权。挥霍岛上的一些智者嗅到了麻烦的气息。他们预见到,为了吃饭并偿还——或者仅仅是支付利息——他们正在堆积的债务,挥霍岛居民最终将不得不每天工作超过8小时。但挥霍岛的居民根本没心情听这种危言耸听。

与此同时,节俭岛的居民开始感到紧张。他们问自己,一个懒散岛屿打出的欠条(IOUs)到底有多可靠?于是,节俭岛改变了策略:虽然他们继续持有一些债券,但他们将大部分债券卖回给挥霍岛居民以换取“挥霍币”,并用这些收益购买挥霍岛的土地。最终,节俭岛拥有了整个挥霍岛。

到了那个时候,挥霍岛居民不得不面对一个丑陋的等式:他们现在不仅必须恢复每天工作8小时以糊口——因为他们已经没有任何东西可供交易——而且还必须额外工作更多的时间来偿还债务,并为那些被草率卖掉的土地向节俭岛支付租金。实际上,挥霍岛不是通过征服,而是通过被购买而沦为了殖民地。

当然,有人可能会争辩说,挥霍岛必须永远运往节俭岛的未来产品的现值,仅等于节俭岛最初放弃的产品,因此这对双方都是公平的交易。但是,既然是一代挥霍岛人享受了免费的午餐,而未来的世世代代都要为此永久买单,这就存在着——用经济学家的话说——相当巨大的代际不公。

让我们用家庭来打个比方:想象一下,我,沃伦·巴菲特,可以让供应我一生消费的所有供应商接受巴菲特家族的欠条,这些欠条将由我的后代以商品和服务(并加上利息)来偿还。这种情况可能被视为巴菲特家庭单位与其债权人之间的公平交易。但我之后的几代巴菲特恐怕不会为这笔交易鼓掌(甚至,上帝保佑,他们可能会试图赖账)。

再回想一下那些岛屿:迟早,挥霍岛政府面对日益增加的债务偿还压力,会决定采取高通胀政策——即发行更多的“挥霍币”来稀释每一枚货币的价值。毕竟,政府会推断,那些恼人的“挥霍债券”只是对特定数量“挥霍币”的索取权,而不是对特定价值货币的索取权。简而言之,让“挥霍币”贬值将减轻岛上的财政痛苦。

这种前景正是我如果是节俭岛居民,会选择直接拥有挥霍岛的土地,而不是其政府债券的原因。大多数政府在道德上会发现,没收外国人拥有的财产比稀释外国人持有的“兑换凭证”的购买力要难得多。相比武力掠夺,暗中窃取(通过通胀)总是更受青睐的手段。

那么,这所有的岛屿寓言与美国有什么关系呢?简单地说,二战后直到1970年代初,我们的运作方式就像勤劳的节俭岛,经常卖到海外的东西比买回来的多。同时我们在海外投资我们的盈余,结果是我们的净投资头寸——即我们持有的外国资产减去外国人持有的美国资产——从1950年的370亿美元增加到1970年的680亿美元(根据当时政府使用的方法统计,后以此修订)。总之,在那个年代,我们国家的净资产,从整体上看,包括了我们境内的所有财富加上世界其他地方的一小部分财富。

此外,由于美国对世界其他地区处于净拥有地位,我们获得了净投资收益,这笔收益叠加在我们的贸易顺差之上,成为了第二笔可投资资金。因此,我们的财政状况类似于一个既储蓄部分工资又将现有储备金的股息进行再投资的个人。

在1970年代后期,贸易形势发生了逆转,产生了约占GDP 1%的逆差。这在当时并不严重,特别是因为净投资收益仍为正值。事实上,借助复利的力量,我们的净所有权余额在1980年达到了3600亿美元的高峰。

然而,从那以后,情况急转直下,过去五年的下滑速度更是急剧加快。我们现在的年度贸易逆差超过了GDP的4%。同样不祥的是,世界其他地区拥有的美国资产比我们拥有的其他国家资产多出惊人的2.5万亿美元。这2.5万亿美元中,一部分投资于索偿凭证——美国债券,包括政府和私人的——一部分投资于房地产和股票等资产。

实际上,我们国家的行为就像一个极其富有的家庭,拥有一个巨大的农场。为了消费比我们产出多4%的东西——这就是贸易逆差——我们日复一日地既在变卖农场的一部分,又在增加我们仍拥有部分的抵押贷款。

为了让大家对2.5万亿美元的外国净所有权有个概念,可以将其与价值12万亿美元的美国上市公司股票,或同等价值的美国住宅房地产,或我估计总计50万亿美元的国家财富进行对比。这些比较表明,已经转移到国外的财富是巨大的——大约占我们国家财富的5%。

然而,更重要的是,按照目前的贸易逆差水平,外国对我们资产的所有权将每年增长约5000亿美元,这意味着赤字每年将使外国人对我们国家财富的净所有权增加约一个百分点。随着这种所有权的增长,流出这个国家的年度净投资收益也将随之增长。这将使我们向世界支付越来越多的股息和利息,而不是像过去那样成为净接收者。我们已经进入了负复利的世界——再见快乐,你好痛苦。

我们在经济学入门课上学过,各国不能长期维持巨大的、不断增长的贸易逆差。据称,到了某一点,消费狂欢国家的挥霍将被汇率调整和债权国不愿接受大手大脚者无休止欠条的态度所制止。对于世界其他国家来说,这确实是运作方式,正如我们在最近几十年看到许多挥霍无度的国家遭遇信贷突然中断那样。

然而,美国享有特殊地位。实际上,我们今天可以随心所欲,因为我们过去的财务行为堪称典范——而且因为我们非常富有。我们的偿付能力和偿付意愿都不受质疑,我们继续拥有堆积如山的优质资产可供交换消费品。换句话说,我们的“国家信用卡”允许我们刷出令人咋舌的金额。但这张卡的信用额度并非无限。

停止这种用资产换取消费品的做法,就是现在,我有一个计划来实现这一点。我的补救措施听起来可能有些取巧,实际上它就是一种换了名字的关税。但这是一种保留了大多数自由市场优点的关税,它既不保护特定行业,也不惩罚特定国家,更不会鼓励贸易战。这个计划将增加我们的出口,并很可能导致世界贸易总量的增加。它能在不导致美元大幅贬值的情况下平衡我们的账目,而我认为若不采取行动,美元大幅贬值几乎是必然的。

我们将通过向所有美国出口商发放我称之为进口凭证(Import Certificates,简称ICs)来实现这种平衡,发放金额等于其出口产品的美元价值。每个出口商再将这些ICs卖给想要将货物输入美国的当事方——无论是国外出口商还是美国进口商。例如,要进口100万美元的货物,进口商需要拥有由100万美元出口额所衍生的ICs。必然的结果是:贸易平衡。

由于我们的出口总额每月约为800亿美元,ICs将大量发行——即每月800亿份证书——肯定会在一个流动性极强的市场上交易。竞争将决定谁会购买这些证书以及他们愿意支付多少钱。(我设想这些证书的有效期很短,可能是六个月,以阻止投机者囤积。)

为了说明目的,让我们假设每份IC售价为10美分——即每出口1美元对应10美分。在其他条件相同的情况下,这意味着美国生产商通过在出口市场销售商品可以比在国内销售多赚10%,这额外的10%来自于他销售ICs的收入。

在我看来,许多出口商会将此视为成本的降低,这将使他们能够在国际市场上降低产品价格。大宗商品类产品尤其会鼓励这种行为。例如,如果铝在国内售价为每磅66美分,而ICs价值10%,国内铝生产商可以在国外市场以约60美分(加上运输成本)的价格销售,仍能获得正常利润。在这种情况下,美国的产出将变得更具竞争力,出口将扩大。在此过程中,就业机会也会增加。

当然,向我们销售产品的外国人将面临更严峻的经济状况。但无论采用何种贸易解决方案,这是他们必须面对的问题——别搞错了,解决方案必须出台。(正如赫伯·斯坦(Herb Stein)所说:“如果一件事无法永远持续下去,它终将停止。”)从某种意义上说,IC计划给了向我们销售的国家很大的灵活性,因为该计划不惩罚任何特定的行业或产品。最终,自由市场将决定什么将在美国销售,以及由谁来销售。ICs只决定销售的总美元金额。

为了看看对进口会发生什么影响,让我们看一辆目前以2万美元成本进入美国的汽车。在新计划下,假设ICs售价为10%,进口商的成本将升至2.2万美元。如果对该汽车的需求异常强劲,进口商可能设法将这笔费用全部转嫁给美国消费者。但在通常情况下,竞争力量会发挥作用,要求外国制造商吸收部分(如果不是全部)这2000美元的IC成本。

IC计划没有免费的午餐:它会对美国公民产生某些严重的负面后果。大多数进口产品的价格会上涨,国内生产的某些竞争产品的价格也会上涨。因此,ICs的成本,无论是全部还是部分,通常都会像税收一样作用于消费者。

这是一个严重的缺点。但是,如果美元继续贬值,或者我们要提高特定产品的关税或实行配额,也会有缺点——在我看来,这些行动方案成功的机会更小。最重要的是,今天进口商品价格上涨的痛苦,与如果我们随波逐流、将国家越来越多的净资产拱手让人最终将遭受的痛苦相比,简直不值一提。

我相信ICs将相当迅速地产生一个高于目前出口水平但低于目前进口水平的美国贸易均衡。这些证书将适度帮助我们所有的行业参与世界竞争,同时让自由市场决定它们中究竟谁最终经得起比较优势的考验。

这个计划不会被净出口国复制,因为他们的ICs将一文不值。主要出口国会以其他方式报复吗?这会引发另一场斯穆特-霍利(Smoot-Hawley)关税战吗?不太可能。在斯穆特-霍利关税法案时期,我们拥有不合理的贸易顺差并希望维持它。现在我们运行着破坏性的赤字,全世界都知道我们必须纠正这一点。

几十年来,世界一直在与惩罚性关税、出口补贴、配额、盯住美元的汇率等不断变化的迷宫作斗争。许多主要出口国长期以来一直在使用这些抑制进口和鼓励出口的手段,试图积累越来越大的盈余——但这并未引发重大的贸易战。肯定不会因为一个仅仅旨在平衡世界上最大的贸易债务国账目的提议而引发贸易战。主要出口国过去表现得相当理性,它们将继续如此——尽管像往常一样,试图让我们相信它们会采取非理性行为可能符合它们的利益。

IC计划的可能结果是,出口国——在经过一番最初的姿态后——将把聪明才智转向鼓励从我们这里进口。以中国为例,今天它每年向我们出售约1400亿美元的商品和服务,而只购买250亿美元。如果ICs存在,中国的一条出路就是购买1150亿份证书来填补缺口。但它也可以通过减少对美出口或增加对美采购来减少对ICs的需求。后一种选择对中国来说可能是最容易接受的,我们也应该希望如此。

如果我们的出口增加,ICs的供应量因此扩大,其市场价格就会被压低。事实上,如果我们的出口充分扩大,ICs将变得一文不值,整个计划也就失去了意义。当面对这种可能性时,重要的出口国可能会迅速消除它们目前用来抑制我们出口的机制。

如果我们实施IC计划,我们可以选择几年的过渡期,在这期间我们要故意维持相对较小的赤字,这一步骤将使世界能够在我们逐渐达到目标的过程中进行调整。在执行这一计划时,我们的政府可以每月拍卖“奖金”ICs,或者干脆将它们送给需要增加出口的欠发达国家。后一种做法将提供一种可能特别有效且受赞赏的对外援助形式。

在结束之前,我要再次提醒大家,我以前喊过一次“狼来了”。总的来说,美国末日论者的“击球率”(预测准确率)极低。对于那些怀疑我们经济潜力或韧性的人,我们的国家一直让他们看起来像傻瓜。许多悲观的预言家只是低估了那种让我们克服看似不祥之兆的活力。我们仍然拥有一个真正了不起的国家和经济。

但我相信,在贸易逆差问题上,我们也面临着一个将考验我们要找到解决方案的所有能力的问题。美元的温和贬值无法提供答案。诚然,它会在一定程度上减少我们的贸易逆差,但不足以阻止我们国家净资产的流出以及随之而来的投资收益赤字的增长。

也许有比我的方案更合理的解决方案。然而,一厢情愿的想法——以及它通常的伴侣,“吮吸拇指”(意指无所作为)——并不在其中。就我目前所见,必须采取行动阻止我们国家财富的快速流出,而ICs似乎是完成这项工作最不痛苦和最确定的方式。请记住,这不是一个小问题:例如,按照世界其他地区目前在美国进行净投资的速度,它们每年可以购买并储存我们近4%的公开交易股票。

在评估伯克希尔的商业选择时,我的合伙人查理·芒格(Charles Munger)建议我们要密切关注他那句半开玩笑的愿望:“我只想知道我会死在哪里,这样我就永远不去那个地方。”制定我们贸易政策的人应该听从这一警告——并远离挥霍岛。

沃伦·巴菲特是伯克希尔·哈撒韦公司董事长兼首席执行官。《财富》特约编辑卡罗尔·J·卢米斯也是伯克希尔的股东,她与巴菲特合作撰写了本文。

对进口凭证方案的评价

国际收支

巴菲特在文中对美国宏观经济失衡的分析,基于国际收支平衡表(Balance of Payments)的基础会计准则。

- 净资产转移的必然性: 文章正确指出了经常账户(贸易)逆差必须通过资本账户顺差来融资。即美国通过向外国出售资产(股票、债券、房地产)或增加对外负债来支付超出产出的消费。

- 长期债务周期的负面影响: 巴菲特强调了投资收益(Investment Income)的逆转风险。随着外国持有的美国资产增加,美国从“净债权国”转变为“净债务国”,导致国民总收入(GNI)将因支付利息和股息而低于国内生产总值(GDP)。从长周期债务模型来看,这一趋势确实削弱了国家长期的偿付能力和财富积累。

市场化的关税体系

进口凭证(IC)方案是一种通过数量管制实现的市场化关税机制:

- 强制性贸易平衡: IC机制通过将进口许可与出口业绩挂钩,从数学上锁定了经常账户的平衡,消除了长期逆差的可能性。

- 财政中性下的财富转移: 该计划等同于对所有进口商品征收关税,并同时将这笔收入全额转移给出口商作为补贴。这改变了国内贸易部门(可贸易品)的相对价格,旨在提高美国出口产品的价格竞争力。

金融层面的系统性缺陷

特里芬难题(Triffin Dilemma)的约束: 全球贸易和金融体系依赖美元提供流动性。美国作为储备货币发行国,必须通过长期的贸易逆差向全球输出美元。IC计划强制平衡贸易,意味着美国停止向全球净输出美元流动性。这将导致全球美元短缺,进而引发全球通缩或迫使各国寻求替代货币,从根本上动摇美元体系的根基。

意图:强制置换持有标的

巴菲特方案的本质,是利用价格机制(IC作为补贴),改变外国持有者的激励结构(购买资产 -> 购买商品)。

- 现状: 外国人持有美元 -> 购买美债或其他资产(资本账户回流) -> 积累对美债权。

- IC计划后: 美国商品价格下降(含IC补贴) -> 外国人持有美元 -> 购买美国商品(经常账户回流) -> 债权结清。

- 宏观效果: 这确实会迫使全球盈余国(如当年的中国、日本)将其持有的美元盈余用于消费美国商品,从而减少对美国金融资产(国债、股票)的净购买。这将导致美国经常账户赤字消失,同时资本账户盈余(外资流入)也随之消失。

后果:美债收益率的重定价 既然外国人“少买美国资产”,美国金融资产的边际买家将消失。

- 供需失衡: 美国国债失去了最大的海外边际购买力。

- 价格调整: 为了吸引买家,美债必须提供更高的收益率。这将导致美国国内融资成本大幅上升,资产价格(股票、房地产)面临去杠杆压力。

监管套利(Regulatory Arbitrage)

经常账户与资本账户的界限模糊化 IC计划的核心是补贴“出口”(经常账户)。市场主体会极其理性地试图将“出售资产”(资本账户)伪装成“出口商品或服务”,以骗取IC补贴。

- 操作路径:

- 正常情况: 美国公司以1亿美元向外国公司出售一栋大楼或一家子公司(资产交易,无IC)。

- 打包操作: 美国公司不直接出售资产,而是签署一份总价0.9亿美元的“长期技术咨询与知识产权授权协议”(服务贸易出口,获取0.1亿的IC补贴)。

结果: 原本属于资本账户的交易被“洗”进经常账户。

- 估值难题: 实物商品(如大豆、飞机)有国际公允价,难以造假。但服务贸易、知识产权、复杂的金融结构产品的定价具有高度主观性。

- 套利后果: 如果“打包”盛行,IC将被大量虚假出口或资产伪装的出口套取。这会导致IC供应激增,价格暴跌,最终导致巴菲特的限制进口机制失效(因为进口商可以极低成本买到IC)。

综合评价

- 贸易平衡: 巴菲特方案在理论上确实能通过补贴机制,激励外国人用手中的美元去消费美国商品,而非单纯囤积美债。这在短期内有利于美国制造业复苏。

- 资产价格: 该方案的代价是切断了美债的海外资金来源。如果外国人“多买商品、少买资产”,美国国内的低利率环境将终结,资产价格泡沫将破裂。

- 执行漏洞: 在现代复杂的金融和服务贸易体系下,区分“商品出口”和“资产出售”极度困难。资本会通过伪装成贸易流来套取补贴,导致IC市场沦为监管套利的温床,最终可能不仅无法平衡贸易,反而引发金融监管系统的混乱。